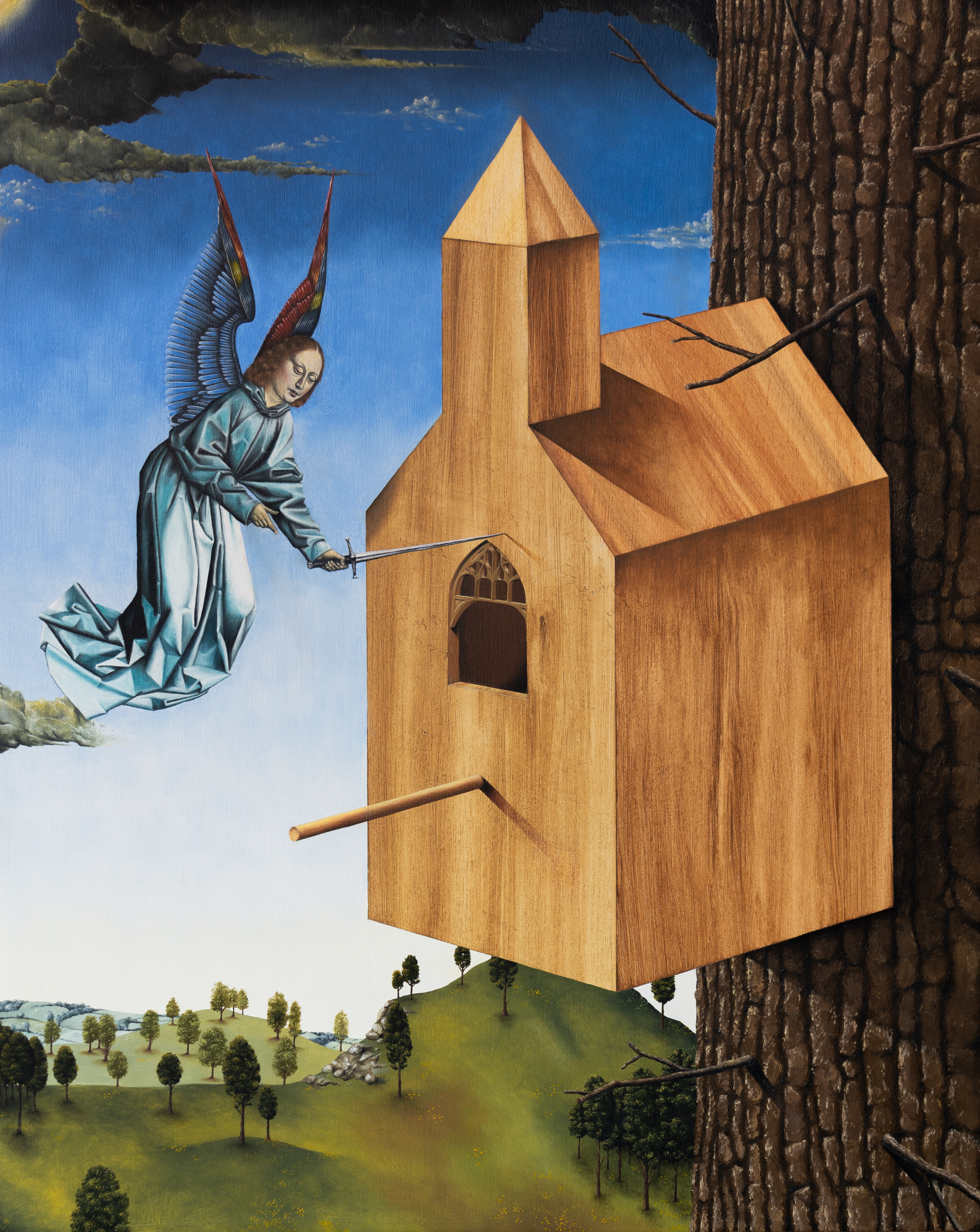

The painterly work of Dittmar Viane is significantly influenced by the Early Netherlandish painting from the 15-16th century. Painters like Dirk Bouts (1410-1475) and Hans Memling (1430-1494) employed distinctive drawing techniques like linear perspective to create a uniquely realist but slightly estranging feel; and being one of the first generations of painters to work with oil paint they developed subtle painterly techniques for chromatic glazing that, combined with the subdued hues of their colors, created an eerie luminescence in their paintings.

Dittmar Viane studied graphic arts and illustration at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent. Having first honed his drawing skills, he turned to oil painting in the final years of his education. Like the Early Netherlandish painters, Viane now works almost exclusively with oil paint and a series of fine brushes. This combination allows him to apply the extremely subtle transitions and details and the glazing technique that gives the works a transparent and lifelike shine. Making its colors slightly darker through the addition of minimal amounts of black paint, he is able to counter the overly brightening effect and visual depth that a glazing can achieve; and at the same time, it binds the colors in his work together.